Sean Carberry: Write Your Own Story

There wasn’t one singular moment — a specific incident that forever changed me. Rather, it was an accumulation over seven years of traveling to places amid conflict, just emerging from conflict, or on the verge of conflict.

Sudan, Colombia, Iraq, Congo, Yemen, Libya, Afghanistan…

It was my job as a journalist covering war and conflict to climb through the wreckage of people’s lives and listen to their tales of trauma. People poured out their hearts about how sadistic militias ransacked their villages, killing and raping along the way. People described walking for miles through jungles to reach displacement camps where they slept on the dirt under rudimentary tents. Men were missing limbs lost fighting to protect their families from insurgents and extremists. There were sickly, malnourished children who couldn’t understand what was happening.

Through it all, focus on the story. Don’t stop to feel, don’t let it sink in. Do the work. Gather facts, hear people’s stories, extract their pain and suffering, report it back to the rest of the world, and move on to the next assignment. Don’t slow down enough to let it all catch up with you.

After years of seeing and hearing the worst of humanity, how do you relate to other people? How do you feel good about the world? How do you return to polite society and pretend everything is fine?

But that’s what I did. After returning to the United States from more than two years in Afghanistan reporting on the war, the destruction of infrastructure and lives, and the deaths of friends and colleagues, I pretended things were fine.

They weren’t.

I was traumatized by all I had seen and experienced. I was altered by spending so much time in dangerous settings. I was angry at a world that perpetrated such horrors on innocent people. I felt alone and isolated, unable to relate to friends and family.

While my professional life progressed with a new job in government and I looked successful from the outside, on the inside I was lost and deteriorating. Gambling, a toxic relationship, self-medicating, I had fallen into all the unhealthy coping, or perhaps avoidance, mechanisms.

In fall 2020, I hit the wall. I was done. I started making plans to end things.

What stopped me? Squeak, my Afghan cat. The thought of abandoning her was enough to give me pause. My decision to rescue her from the streets of Kabul in 2012 ended up rescuing me.

I stepped back from everything to assess my life. I opened up to some close friends and family about the psychological and emotional hole I was in. Just talking, acknowledging out loud that I was hurting, was a relief. I found a therapist, which was important, but equally important was the pause. Taking sick leave and removing the stress of a punishing and unfulfilling job allowed me to see there were other paths. I decided to travel a new one.

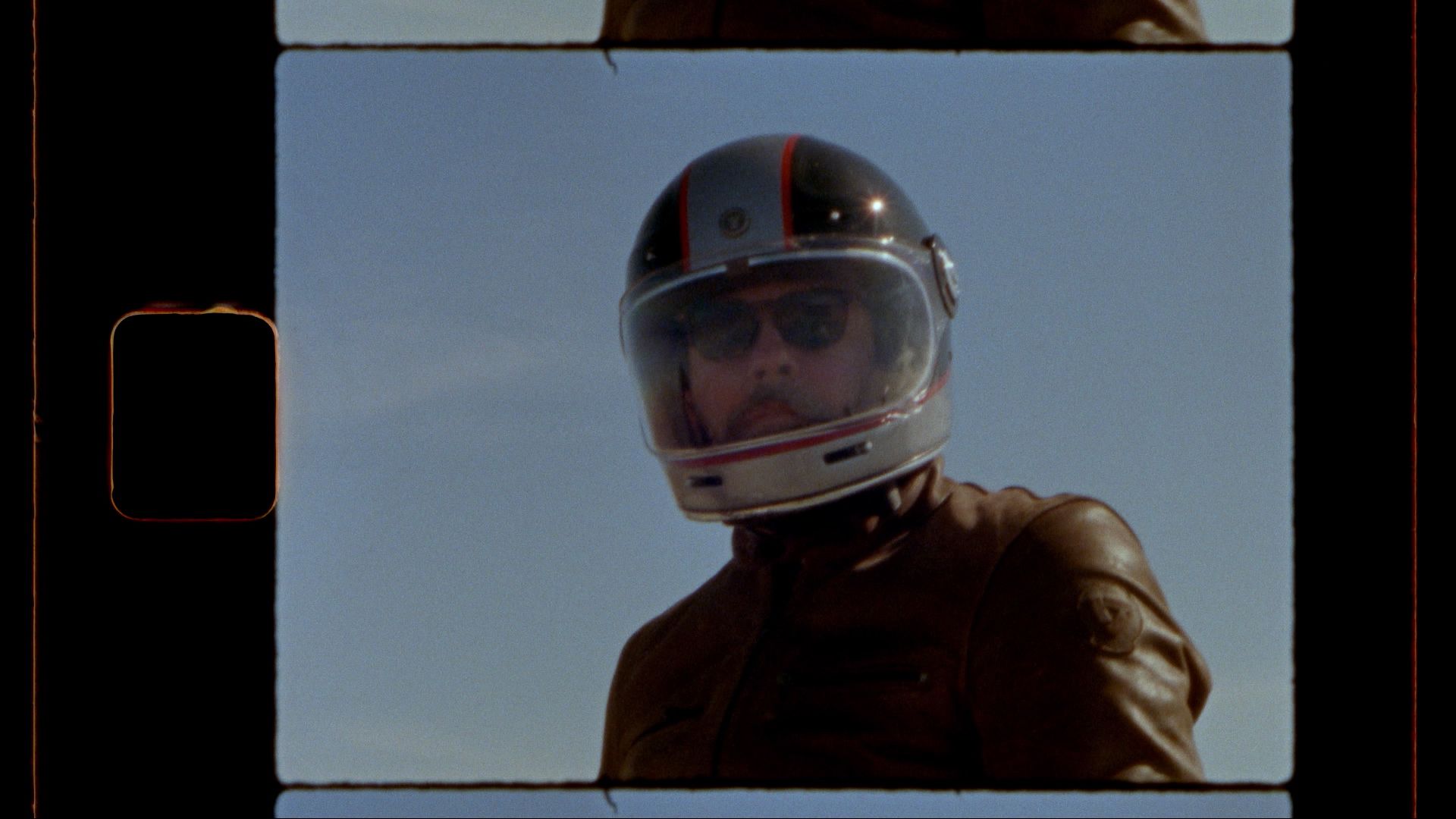

The Distinguished Gentleman’s Ride and Movember have been part of my journey. Just before I hit bottom, I participated in the 2020 ride. It was my third.

When I initially learned about the ride, its purpose, and the charity it supported, I was in. Prostate cancer has not been kind to my family. My maternal grandfather died at 66, when I was in high school. My father is a survivor, treated successfully when he was a few years younger than I am today. His father had a mild strain late in life.

So, when I started participating in the ride and supporting Movember, I was focused on the prostate cancer mission since it’s something I have to keep an eye on myself.

However, in the years after my first ride, Movember increased its focus on men’s mental health as my mental health was deteriorating. After the 2020 ride, when I was falling apart, I realized that I was no longer a rider supporting the cause, I was the cause. I was a man contemplating suicide.

" Since then, the Distinguished Gentleman’s Ride and Movember have been part of my healing process, part of my purpose. "

Participating in Movember events, raising money, encouraging others to join and support Movember, it’s all been fulfilling. But what has been most fulfilling has been opening up and telling my story. One of the ways I climbed out of my hole was to write a book about my experiences as a foreign correspondent and to talk candidly about the mental health impacts of that work. Organizations that send civilians to work in hostile environments have a poor track record of providing mental health awareness and care for their personnel. That needs to change, and change happens when people tell their stories.

And that’s exactly what Movember is working to do — encourage men to tell their stories, to open up about their health, and to recognize that it’s OK not to be OK. By telling my story to the DGR and Movember community, I am hoping it will empower others to talk, to seek help, to stop suffering in silence. We are only alone if we choose to be.

Support Sean’s efforts to raise funds and awareness for men’s health.

If you or someone you know is in crisis or needs emotional support we urge you to head to movember.com/getsupport for crisis support options. To speak with someone immediately, contact your local 24-hour support service.